The Hidden Costs of Waste: From Pollution to Profits

Written on

Chapter 1: The Waste Industry Exposed

When you finish a Coke and toss the bottle aside, you might think it’s gone for good — but that’s far from the truth. Your discarded item transforms into a valuable commodity for the waste industry, which seeks to capitalize on every piece of trash. Items deemed salvageable might end up being sold worldwide; a bottle from a wealthy nation could find its way to a recycling plant in Southeast Asia or Eastern Europe, potentially re-emerging as a toilet seat or trendy sneakers. If it’s not recycled? It may end up in an illegal dump in places like Malaysia or Turkey, where impoverished waste pickers — many of whom are children — sift through heaps of Western refuse.

For decades, what many believed was being recycled actually ended up in poorer countries with cheap labor and lax regulations, creating a form of ‘toxic colonialism.’ The waste clogging rivers in Asia could very well include your own. Alarmingly, only about 20% of household waste is recycled worldwide.

Why the deceit? Waste is a term shrouded in negativity, something we instinctively shy away from, leading to the waste industry operating in obscurity. Garbage trucks make their rounds during the early hours or late at night, while facilities are often situated in the periphery of our awareness. We offload our waste onto the marginalized.

Despite its hidden nature, the waste sector is a multi-billion-dollar industry. The adage “one person’s trash is another’s treasure” rings true for those willing to dive into this murky world. It's perhaps this allure that has historically made waste a hotspot for criminal activity.

Section 1.1: Crime Within the Waste Sector

Waste has always been a magnet for crime, thriving on the combination of hefty profits, low-skilled labor, and minimal scrutiny. The general apathy towards rubbish means that few inquire about what happens to it.

In the United States, the mafia dominated the waste trade on the East Coast for decades, using private garbage collection as a front for organized crime. This covert operation generated hundreds of millions each year, with any disruptions met with brutal threats, including beatings and even murders. By the 1990s, corporate giants like Waste Management Inc. found the East Coast largely inaccessible.

Similar narratives unfold globally. The Yakuza manipulates the waste sector in Japan, while MS-13 in Honduras uses landfills as a cover. In Buenos Aires, the Chinese supermarket mafia resorted to violence over territory disputes, dumping a body in a landfill, discovered by two homeless individuals rummaging through trash.

In Italy, waste crime is closely tied to organized crime. During the 1980s, Italian gangs began importing waste from countries like Germany and Australia, only to dump it in nations such as Ghana and Egypt. The Ndrangheta mafia was notorious for sinking ships laden with illegal toxic waste off the coasts of Italy and North Africa. In Campania, the Camorra mafia buried over 10 million tonnes of hazardous waste, leading to a spike in cancer cases and earning the region the nickname ‘Triangle of Death.’

In the UK, waste crimes are rampant enough that a dedicated Joint Unit for Waste Crime was established in 2021. The government intercepts approximately 500 illegal waste shipments each year, monitoring around 1.3 million cases of illegal dumping or ‘fly-tipping.’ Among the 60 organized criminal gangs involved in waste crimes, 70% were linked to money laundering. Reports even surfaced of a criminal organization exporting waste from the UK to Turkey, which was allegedly used to smuggle drugs, banking on the assumption that customs wouldn’t scrutinize garbage closely.

The video "2022 VCAC - The Dos and Don'ts of Universal Waste Management" delves into effective strategies for managing universal waste, shedding light on the best practices and pitfalls to avoid in waste management.

Section 1.2: The Corporate Face of Waste

From ancient civilizations to the present, waste has chronicled human history. The post-World War II era marked the rise of plastic, flooding our lives with unprecedented waste and reshaping our relationship with it. The term “disposable,” once linked to non-essential items, gained a new, troubling significance. The culture of “throwaway living” became entrenched as plastic infiltrated every aspect of daily life. Ironically, the waste industry didn’t just manage the byproducts of the modern economy; it actively fueled its growth. Corporations transitioned from crafting durable products to producing cheap, disposable goods, promoting a culture of planned obsolescence, while knowing the fallout would impact consumers, not their profits.

The modern economy is essentially built on waste.

In response to the rising litter crisis of the 1980s, Big Plastic invested millions in recycling initiatives. However, this was not a genuine effort but a strategic maneuver to sidestep potential bans. Internally, they recognized the challenges of recycling due to plastic degradation, sorting difficulties, and mixed material separation. Recycling became a smokescreen, a distraction designed to mitigate public concern while shifting focus away from environmental issues.

As Larry Thomas, former president of the Society of the Plastic Industry, stated to NPR: “If the public believes recycling is effective, they won’t be as concerned about the environment.”

A predictable pattern emerged: grand promises of increased recycling and new facilities, only to be abandoned when attention waned. Internal documents from Coca-Cola revealed a calculated approach to legislative changes — monitoring, preparing, and pushing back against impactful measures like deposit return schemes.

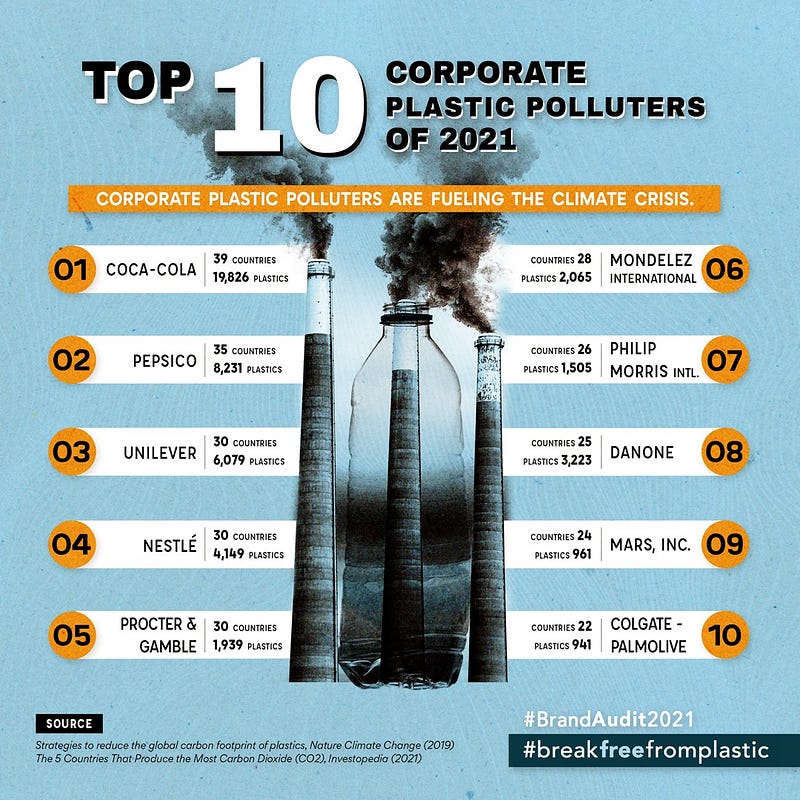

In 2016, a leaked internal document to Greenpeace illustrated Coca-Cola’s — the leading plastic polluter globally — strategic approach to impending legislation. This trend isn’t exclusive to Coca-Cola; companies like PepsiCo and Nestlé have also failed to meet recycling targets. Media outlets often highlight their pledges, but accountability for unmet promises remains scarce. The plastic industry’s false commitment to recycling serves to maintain the illusion that they are effectively tackling the waste crisis.

Section 1.3: The Global Waste Shift

So, what’s the strategy for a leading waste-polluting nation burdened with tons of mixed, contaminated, and unprofitable-to-recycle plastics? Offload the problem onto someone else.

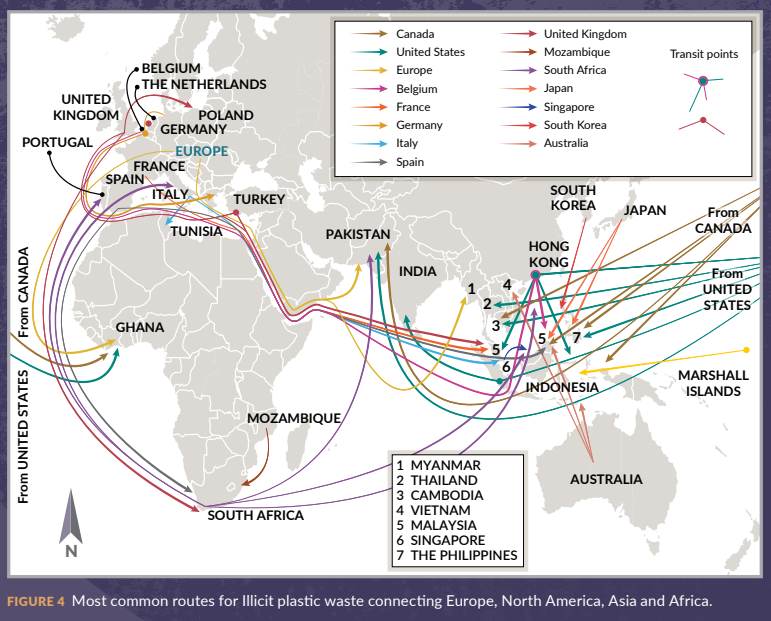

By the 1980s, Western countries were inundated with waste. The global economy offered a convenient solution: export the issue. Container ships that once returned empty began sailing back full of trash. For decades, China absorbed 47% of global plastic waste exports. However, in 2018, China implemented the ‘National Sword’ policy, closing its doors due to contamination and environmental concerns, causing a shockwave in the global waste industry as recycling markets collapsed.

The video "DTSC Workload Analysis - Hazardous Waste Management Program - Part 1" examines the complexities of hazardous waste management and the challenges faced by regulatory bodies.

Following China’s closure, a surge of waste sought new homes in countries like Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam, all grappling with high rates of waste mismanagement. Trash overflowed into open landfills, and recycling facilities struggled with inadequate oversight, exacerbated by smuggling operations connected to organized crime. The cycle continued, shifting waste from one nation to another — Turkey, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Mexico, El Salvador — regardless of agreements or container returns.

No country wants to be the world’s dumping ground. Consequently, efforts to address the issue culminated in 2019, when 187 countries signed a Basel Convention amendment to restrict plastic exports. However, both the United States and China remain among the few nations that have not signed.

Yet, the flow of rubbish continues. The profitability of the waste industry ensures that it remains a lucrative venture.

Chapter 2: The Unyielding Waste Crisis

February 2, 1968, marked a pivotal moment for one of the world’s iconic cities, which had begun to resemble a slum. For the first time since the 1931 polio epidemic, city officials declared a state of emergency. It took a week for the realization to sink in: the garbagemen were winning. The city capitulated, and the strike concluded. In this metropolis of towering skyscrapers and financial prowess, it was the sanitation workers who emerged as the unsung heroes.

The New York Times lamented: “This greatest of cities must surrender or see itself sink in filth.”

We are drowning under a staggering scale of waste production. Globally, we generate 2.01 billion tonnes of solid waste each year, averaging 0.74 kilograms per person per day. In the United States, the most wasteful nation, individuals produce a staggering 2 kilograms daily. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries represent only 16% of the global population, yet they account for 30% of worldwide organic waste. The wealthier a nation becomes, the more waste it generates. As developing nations grow wealthier, this issue is poised to intensify, with projections indicating an additional 1.3 billion tonnes generated annually by 2050, much of it in the Global South.

Consider the ubiquitous plastic bottle: over 480 billion are sold each year, equating to a million bottles every minute. And that’s merely one of countless items in our daily lives that demand management.

This reality has led to waste management evolving into a corporate industry dominated by a handful of multinational corporations: there’s an unending supply of waste, yet no one wants to confront the unpleasantness of it. Despite projecting a respectable image, the industry is riddled with legal disputes and allegations of criminal activity, raising ethical and legal concerns. Waste Management Inc. in the US has faced charges ranging from antitrust violations to bribery, settling over 200 cases, including a notorious $30 million lawsuit for accounting fraud in 2005. In the UK, Biffa was found guilty of attempting to export contaminated wastepaper to China and was implicated in the country’s largest modern slavery case.

In conclusion, waste is a profit-driven global dilemma, with corporate interests frequently overshadowing environmental and humanitarian considerations.

Chapter 3: The Horror of Our Waste

Archaeologists have unearthed our history through waste: broken weapons, shattered pots, and food scraps with bite marks still imprinted in bones. Waste offers a glimpse into our lives: how we lived, what we ate, and how we interacted with one another.

The contemporary horror story we are crafting through our waste is a disturbing reflection of modern society. Waste mismanagement in landfills contributes to approximately 6% of global emissions, surpassing the combined emissions of the shipping and aviation sectors. If waste were a nation, it would rank as the third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide worldwide, trailing only the USA and China.

One of the most alarming statistics is that one-third of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted globally. Roughly 13,800 square kilometers — an area larger than Qatar — is devoted to growing food that ultimately goes to waste. This uneaten food could sustain two billion individuals. Yet, according to the World Food Programme, over 345 million people face severe food insecurity, and as many as 783 million go hungry, with approximately 9 million lives lost to hunger annually, including 3.1 million children.

Moreover, wasting food equates to wasting the resources, time, and energy invested in its production. Agriculture consumes 70% of the world’s freshwater supply, making food waste a significant drain on both freshwater and groundwater resources. Discarding just one kilogram of beef represents a loss of 25,000 liters of water used for its production. The ongoing carbon emissions, primarily from the fossil fuel industry, have exacerbated climate change, leading to an imminent water crisis, with demand anticipated to exceed the fresh water supply by 40% by decade’s end.

Addressing our waste crisis goes beyond merely cleaning litter from our rivers and oceans (although that is crucial). Waste intertwines with climate change and food security. Waste signifies life and death.

It is imperative that we raise our voices to confront this horrifying narrative. Systemic changes are essential in the waste industry, global economics, and politics. Only through collective action, amplified by a clarion call for change, can we hope to alter the outcome of this modern horror story.

Until then, waste will continue to accumulate in an endless, obscure mass.

Be heard.

Thank you for your attentive reading and support! Join the 400+ Antarctic Sapiens community for weekly insights and thought-provoking content.