Understanding Schizophrenia: A Neurodevelopmental Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: The Nature of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is thought to stem from a mix of genetic vulnerabilities and environmental triggers. The disorder's development is primarily considered neurodevelopmental, as indicated by increased incidences of adverse events surrounding the prenatal and perinatal stages, along with observable cognitive and behavioral issues during childhood and adolescence. Notably, there's a lack of evidence supporting a neurodegenerative process in the majority of those diagnosed. Recent investigations into neurodevelopmental mechanisms suggest that there isn't a single gene or factor responsible for this intricate biological process. Rather, it is the interplay of genetic and environmental elements that disrupts normal development early in life, leading to molecular and structural alterations. These changes pave the way for divergent developmental trajectories, ultimately culminating in the clinical presentation of schizophrenia.

Section 1.1: The Impact of Prenatal Factors

Research indicates that individuals conceived during the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945 faced a doubled risk of developing schizophrenia, affecting both genders (Susser et al. 1996). Interestingly, exposure to moderate malnutrition during early pregnancy or severe malnutrition later in pregnancy did not correlate with increased risk. The heightened risk linked to early pregnancy malnutrition seems particularly relevant to schizophrenia rather than other psychiatric disorders. However, it remains uncertain if other famine-related factors may have influenced the offspring's vulnerability to schizophrenia. The unique context of this study complicates efforts for independent verification.

Maternal Infection: A series of studies starting in 1988 (Mednick et al. 1988) noted a higher-than-expected incidence of schizophrenia among children whose mothers were in their second trimester during the 1957 influenza outbreak. Nonetheless, later investigations have struggled to consistently confirm a connection between the timing of pregnancy and influenza exposure (Morgan et al. 1997, Selten et al. 1998, Jablensky 2000). Furthermore, there have been methodological critiques of the studies that reported positive associations (Crow 1994, McGrath & Castle 1995). Notably, two studies focusing specifically on children of mothers known to contract influenza during the 1957 outbreak did not observe an increased risk of schizophrenia (Cannon et al. 1996, Grech et al. 1997), despite their smaller sample sizes. More recent findings suggest a potential link between maternal rubella infections and increased schizophrenia risk (Brown et al. 2000), as well as higher levels of IgG and IgM immunoglobulins in mothers of later diagnosed individuals (Buka et al. 2001). However, conclusive evidence supporting an infectious in utero cause of schizophrenia remains elusive.

Section 1.2: Recognizing Symptoms

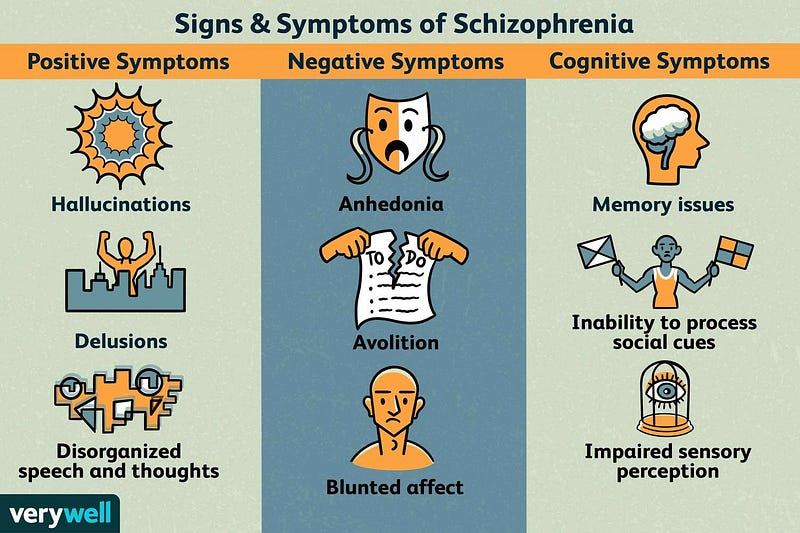

Symptoms of schizophrenia can include:

- Hallucinations

- Delusions

- Disorganized thinking

- Lack of motivation

- Slowed movements

- Altered sleep patterns

- Poor personal grooming or hygiene

- Changes in body language and emotional expression

Chapter 2: Social Behavior and Schizophrenia

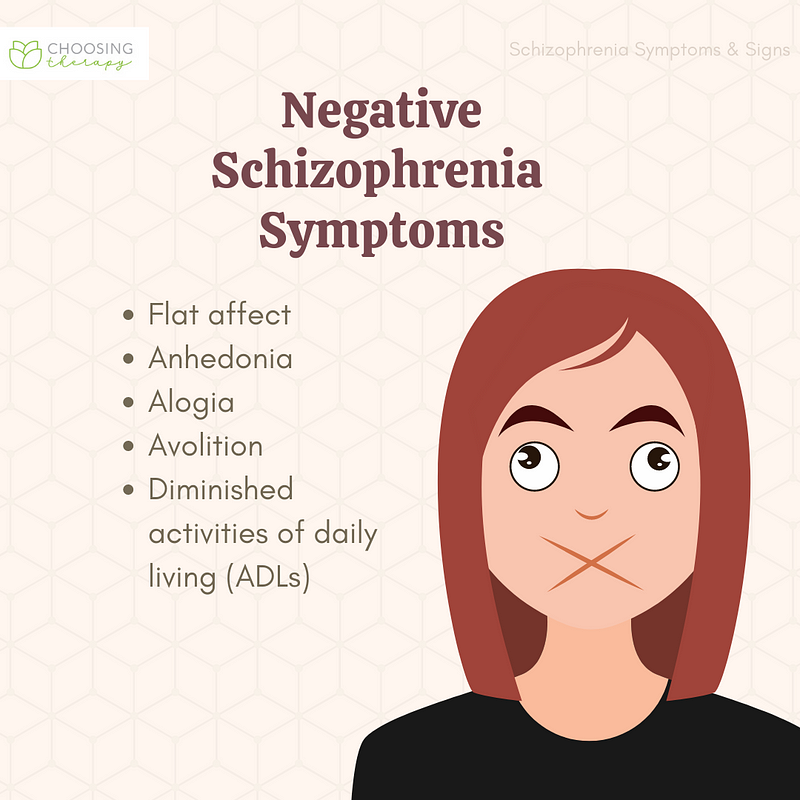

Negative Symptoms and Social Abnormalities:

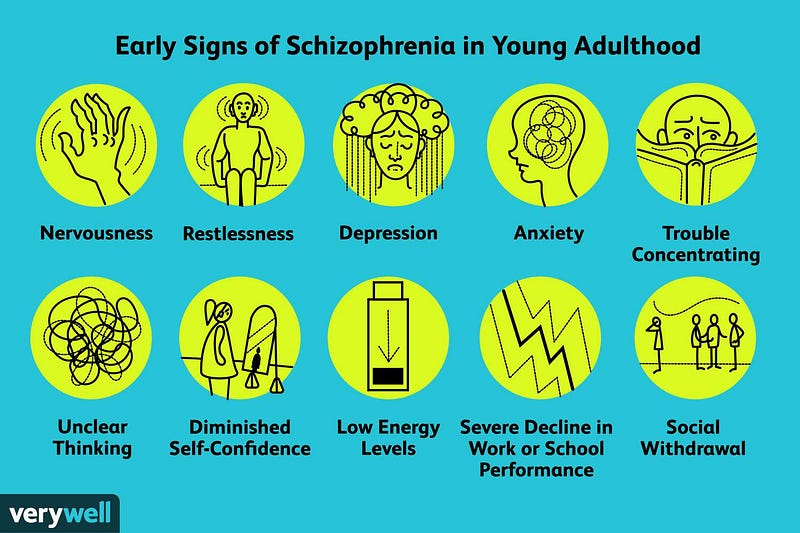

In a study involving individuals born in 1946, those who later developed schizophrenia displayed specific social traits. At ages 4 and 6, they tended to play alone; at age 13, they perceived themselves as less socially confident; and by age 15, teachers noted them as being more socially anxious (Jones et al. 1994). Similarly, in a British cohort from 1958, children who later faced schizophrenia were often labeled by teachers as exhibiting socially maladaptive behaviors as early as age 7 (Done et al. 1994). Boys showed overactivity at ages 7 and 11, while girls were more withdrawn by age 11. In contrast, children who later developed affective psychoses did not exhibit notable differences from their peers at these ages. The Danish High Risk Project (Olin & Mednick 1996) also found that girls destined to develop schizophrenia were seen as more withdrawn and anxious, while boys were perceived as more disruptive and inappropriate (Malmberg et al. 1998). The combination of these factors significantly increased the risk of developing schizophrenia. However, it's essential to recognize that 79% of the sample reported experiencing at least one of these social challenges.

These social behavior abnormalities might not simply be early indicators of schizophrenia; many of these behaviors were identified over a decade before the disorder manifested. It remains unclear if these social difficulties stem directly from the underlying disease process or if they act as psychological risk factors. One theory posits that individuals with less social engagement may have fewer opportunities for reality testing and correction of paranoid thoughts, potentially contributing to the development of schizophrenia.

This video discusses the relationship between neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration in schizophrenia, providing insights into how these processes may influence the disorder.

This video explores the etiology and pathophysiology of schizophrenia, focusing on neurodevelopmental, structural, and neurochemical factors that contribute to the condition.