# Understanding the Dunning-Kruger Effect: Why Confidence Misleads

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dunning-Kruger Effect Unveiled

"Confidence is often a product of ignorance rather than knowledge." - Adapted from Charles Darwin

In April 1995, McArthur Wheeler attempted to rob two banks in Pittsburgh while covering his face with lemon juice, convinced it would render him invisible to security cameras, akin to using invisible ink. He even claimed to have tested this theory with his Polaroid camera prior to the heists. Unsurprisingly, this notion was absurd, leading to his swift arrest after the banks' security footage aired on the news. “But I wore the juice!” he exclaimed, perplexed by the police's arrival.

Initially, Wheeler was dismissed as just another foolish criminal with a misguided scheme, even earning a spot in the 1996 World Almanac for being among the most foolish. However, David Dunning, a psychology professor at Cornell, and his graduate student, Justin Kruger, identified this incident as a prime illustration of what we now refer to as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

What Constitutes the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

In essence, the Dunning-Kruger Effect describes the phenomenon where individuals misjudge their own competence. Those with below-average skills often overestimate their abilities, while those with above-average skills tend to underestimate how proficient they truly are. In simpler terms, some individuals are oblivious to their own lack of knowledge, while more knowledgeable people assume that others share their understanding. In their foundational 1999 paper, titled “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments,” Dunning and Kruger posited that "the misjudgment of the incompetent arises from a self-perception error, whereas the misjudgment of the highly competent is an error regarding others."

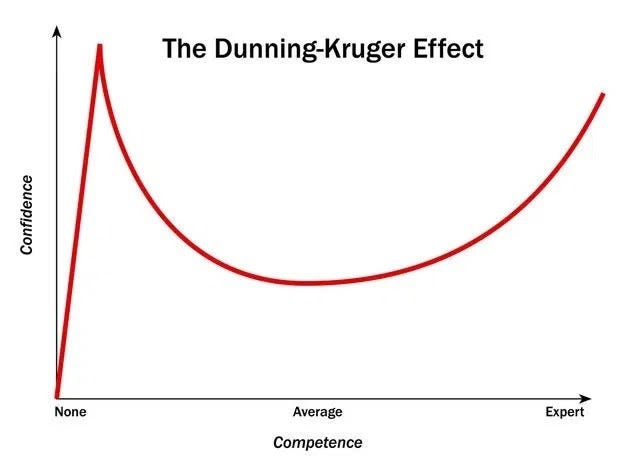

Their initial experiment divided participants into four groups to compare self-evaluations against their abilities in logic, humor, and grammar. The resulting graph illustrates a consistent trend across diverse subjects and groups.

A person's confidence in a specific area does not always align with their actual skill level. Initially, both competence and confidence are low. As individuals acquire basic knowledge, their confidence surges. However, this confidence peaks prematurely, at a stage often referred to as "Mount Stupid." As one learns more about a subject, they begin to grasp its complexities, leading to a sharp decline in confidence, known as the "Valley of Despair." Fortunately, as mastery develops, confidence gradually rises again along what is termed the "Slope of Enlightenment."

The Loudest Voices Often Reside on Mount Stupid

Regrettably, the most vocal individuals often possess high confidence but limited expertise. For instance, commentators across the political spectrum frequently discuss topics they have little understanding of, dominating media cycles without genuine expertise. It is not uncommon to see both liberal and conservative figures speak extensively on science, economics, or foreign policy without being qualified in these fields. How do they maintain such confidence? They exemplify the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Similarly, politicians often project themselves as knowledgeable in areas where they lack expertise. The public recalls instances of Trump dispensing medical advice during the Covid-19 pandemic, despite lacking a medical background. He even irresponsibly advocated for hydroxychloroquine, a drug that was later found to increase mortality rates. In a bizarre statement, Paul Broun, a former member of the House Science Committee, described evolution and cosmology as "lies from the pit of hell." This misplaced confidence can also be attributed to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

This phenomenon is prevalent on social media, where individuals share opinions as if they are authorities. Many of the most vocal contributors on platforms like Twitter or Facebook have merely skimmed a few articles or watched a video, leading to the propagation of unfounded ideas. Some particularly outlandish claims, such as those suggesting that Covid-19 vaccines contain microchips, exemplify this issue. How can individuals lacking a solid scientific foundation exude such confidence? The answer lies in the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Conversely, highly educated individuals often feel like impostors. Those in the Valley of Despair may struggle with feelings of inadequacy, believing that their achievements are due to luck or deception rather than skill. This is especially true for PhD students, who frequently experience significant levels of depression despite their expertise.

Chapter 2: The Impact of Antiscience Movements on Society

Arguably, the most pressing threat to society today is the rising antiscience movement, which is exacerbated by the Dunning-Kruger effect. Those perched on Mount Stupid often wield the most influence, whether by backing antiscience candidates, spreading misinformation, or aiding in the creation of legislation against scientific principles. Consequently, public trust in science has plummeted.

According to the Pew Research Center, as of 2019, only 35% of Americans expressed significant confidence in scientists acting in the public's interest.

In a recent publication in PLoS Biology, Peter Hortez highlighted that numerous scientific disciplines, including climate change, air pollution, and immunology, have faced increased scrutiny and skepticism. Even geology has come under fire, as it contradicts some beliefs that the Earth is only a few thousand years old.

How can society function when so many individuals oppose foundational scientific principles? The answer is straightforward: it cannot. Science is essential for societal development, providing us with electricity, clean water, and medical advancements. Attacking science is akin to dismantling the very fabric of modern civilization.

Hortez argues that addressing these movements, particularly the antivaccine sentiment, requires improved public communication. He suggests that academic institutions should provide media training for scientists and encourage them to engage with the public more actively.

By doing so, we might mitigate the Dunning-Kruger effect, raising the awareness of those in the Valley of Despair to the level of those on Mount Stupid. If this occurs, society could foster a better comprehension of science, ultimately aiding in its progression and cohesion.